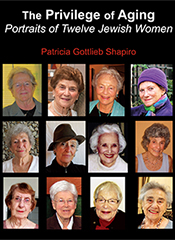

The Privilege of Aging

Portraits of Twelve Jewish Women

Patricia Gottlieb Shapiro

*********

Introduction

On these pages, you will meet twelve women from all parts of the country, women with different lifestyles, experiences, and economic backgrounds. You’ll read about the courage and bravery of a Holocaust survivor, the strength of a teacher to stand up for equal rights for women, the determination of an artist to nurture a long-term relationship.

These women have three things in common: their age—they are all over seventy-five years old—their vitality in coping with the challenges that accompany aging, and their connection to Judaism.

These women are aging well. They lead active, vibrant lives. Their lifelong journeys reveal how their earlier years prepared them for life as older women and how they learned from those experiences. My goal in writing this book is to give you a glimpse into their lives today, to reflect on the reasons for their longevity and vitality, and to learn from their experiences.

We have to wonder: what gave them the support, the spirit and the resilience to overcome challenges and barriers in their long lives? Was it an understanding parent or compassionate teacher? A good education? Growing up in a small town? Or was it simply old-fashioned luck—having good genes or the good fortune to be at the right place at the right time?

Women who are over seventy-five can change how we look at old age. Rather than viewing mature women as dull and static—sitting around watching television all day or waiting for the mail to arrive—many forward thinkers now see old age as a period of growth: a stage of becoming, not just being. This is an innovative way of looking at aging. This is not a denial of old age but a realization that the later years are a developmental period, just like adolescence or midlife. As you will see when you meet the women in this book, they are not only living their lives fully, just as they did when they were younger, but they are continuing to grow and develop as women.

Of course, this is not true for everyone, but for those women who continue to stay productive and involved in life throughout their eighties and nineties, these years can be rich and rewarding. Those are the women we can emulate as role models and those are the women featured in this book.

This project began out of professional curiosity. I had interviewed women from age fifty-five through seventy-five for my last book, Coming Home to Yourself: Eighteen Wise Women Reflect on Their Journeys. I wondered now, what about those over seventy-five? Who are these women? What keeps them going despite physical decline and losses in so many areas of their lives? Is it truly a joy or is it a burden to live into your eighties and nineties? I was also curious about how these older women balanced and blended the many aspects of their lives into a unified whole.

To explore these questions, I wanted to do an in-depth study of their experiences as older women. I was drawn to highly accomplished women: two had taught at the college level, one was a New York Times bestselling author, another a physician at a time when very few women enrolled in medical school. But when I interviewed Bea Klein, a homemaker from Las Cruces, something shifted for me. It brought back many memories of my mother, who was a smart woman and content to spend her days focusing on my father, my sister and me. Like Bea, my mother did not have a college education. Rather than having a career, she did a lot of volunteer work. In fact, she and Bea even volunteered at the same places: the hospital auxiliary and the synagogue. Their pride and joy were their husbands and children.

I wonder what my mother would have been like if she had survived past age seventy-one. Would she have also led a rich, full life like the women I interviewed had she lived into her eighties or nineties? What traits or characteristics ensure longevity not in years alone but in quality of life? My professional curiosity in this project now deepened to include a much more personal motivation to explore the answers to the questions I posed.

Did these women have better genes or did my mother not have the passion, resiliency or meaning in life that can lead to long years? Many women received satisfaction from their roles as homemakers, mothers and wives during the 1940s and ‘50s, but let’s not forget the other women who were stifled in those roles, who Betty Friedan touched when she spoke of “the problem that has no name.”

Women who chose (or had little choice) to be homemakers deserve our respect as much as those who earned Ph.Ds. Our society does not value them equally, however, even in the twenty-first century. This is not the place for a discussion of the mommy wars except to note that some of the women who lived into their eighties and nineties who led so-called ordinary, 1950s-housewife-type lives—like June Cleaver—must have had something in their earlier decades that prepared them for a fulfilling late age. It could be genes, experiences, relationships, or education. And the women who have led more “interesting,” high-achieving lives also must have had earlier experiences that led them to the same place today.

It seems to me that it was not the graduate education or the career successes that led to their longevity, but other ingredients that they shared with the so-called ordinary women. Perhaps both had strong parents, challenging teachers, solid relationships, or an experience that they faced and overcame that built their long-lasting resilience. In other words, it might not be the external events of a woman’s life but the internal, emotional, or psychological forces and influences that forge the resilience that provide the basis for a woman to live well for nine or ten decades.

The Face Of Aging Today

Everyone knows that baby boomers (those born between 1946 and 1964) are changing the face of aging, that they are transforming the way we regard the years between sixty and seventy, and how we view retirement. And they’re transforming it in a noisy way; we all know they are there. They now number thirty-five million, about half of whom are women.

But baby boomers tell only part of the story. There is also an unsung group of individuals who are living longer and leading active, engaged lives: those over the age of seventy-five. According to the National Jewish Population Study (2011), they comprise nine percent of the Jewish population. That is almost 500,000 people and women form more than half of this older group. These women remain invisible in our youth-oriented culture; you do not usually read about them in the media, but they personally touch many of us. When I was looking for women in this age bracket to interview for this book, so many people said to me, “Oh, you must meet so-and-so. She is an amazing woman!”

These women are all around us and we can learn from their examples. Not only because they are amazing but also because younger generations need role models to show us how to live the years past age seventy-five. We desperately want and need advice and guidance. We want to know what it’s really like to have outlived your best friends, to see a great grandchild struggle, to cope with an aging body.

And we want to know how they contend with the existential questions of aging. In her book Composing a Further Life, writer and cultural anthropologist Mary Catherine Bateson raises an essential question for older women to ponder: “How do I grow older and remain myself—or rather, how in growing older do I become more truly myself, and how is that expressed in what I do or say or contribute?”

These are important questions for us to reflect on as we age, because women have not lived this long in large numbers before. There is no template for these later years: That’s the rub and the opportunity—for all of us.

The Secret To Longevity

Everyone wants to know the secret to a long life. Is it eating yogurt for years? A particular DNA? A study of long-lived Ashkenazi Jews has found that those who drank slightly more and exercised less than their average counterparts lived longer. But their longevity had nothing to do with their religion.

In central Italy, people believe their dietary habits hold the key to their longevity. No one in Campodimele takes short cuts. They bring down logs from nearby hills on horseback to fuel their wood-burning stoves, make their own olive oil and pasta, and harvest their own grain. Meals can take hours to prepare. Many Japanese, on the other hand, credit their diet of vegetables and tofu and other soy products as the reason they live so long.

Here in the United States, it’s not diet but resilience that researchers are beginning to realize might hold the secret to living a long life. According to Al Siebert, Ph.D., founder of The Resiliency Center and author of The Resiliency Advantage, “Longevity research is showing that adults with psychological resiliency age more slowly, live longer, and enjoy better health. A strong inner spirit can carry an aging body a long ways.”

A related study by British epidemiologist Michael Marmot, seen in his 2005 book, The Status Syndrome: How Social Standing Affects Our Health and Longevity, provided evidence that the people who age successfully do so because they have considerable control over their lives as well as strong social support. Taking control is an aspect of resilience: It is an active role rather than passively waiting on the sideline for something to happen. It is this sense of agency, of get-up-and-go, that serves people well in old age. And certainly, monetary security helps as well.

Numerous studies have shown the importance of social support throughout the life span. This holds true as we age. Last summer when I was at the Jersey shore, an acquaintance, who is in her early eighties, invited me to meet her bridge group. They were convening in her apartment the following evening. These nine Jewish women, between the ages of seventy-five and eight-five, have been playing bridge together for over fifty years. They were attractive and took care with their appearance. When I told them about the book, they were fascinated and full of questions. Then we went around the room and each woman spoke for a few minutes about her life.

They had all lived in the Atlantic City/Margate area for most of their lives. Many left to go to school and then returned. Most of their children followed the same pattern and have settled in the area. Every one there had experienced some kind of hardship: one woman had been homeless and lived out of her car for a while, several had lost children and husbands, a few had serious health issues.

“What helped you overcome adversity?” I asked when they had finished speaking. They all agreed: their small town roots and their long-standing friendships. The security of living “where everyone knows your name” and the support of good friends created a foundation that enabled them to rebound from whatever challenging situations they encountered during their long lives.

The Only Constant Is Change

The only thing that remains unchanged in our lives—no matter our age, religion, lifestyle, economics or culture—is change. Some changes are thrust upon us; others we welcome willingly. Both invite a deeper understanding of ourselves, if we’re open to such reflection.

As we have seen in recent years, everything—from the climate to politics to electronics—is constantly in flux. We have so little control. We can only manage our responses: how we accept and adapt to shifts, whether we roll with the punches, or remain rigid and static can affect our lives in ways both beneficial and destructive.

From my research and writing about psychological topics and women’s issues, I believe that the more adaptable we are, the longer we’ll live. The more open to transitions and the more willing to try variations, the more likely we are to grow and expand. This attitude keeps us young and vibrant in mind and spirit, and better able to cope with the physical changes of aging. After years of research on resilience in children and adolescents, recent studies now point to resilience as a key factor in explaining who thrives among the oldest of the old.

Other research has shown that those women who experienced the most discontinuity and change earlier in life became most vital later, while those who clung to a single outdated role ended up frustrated and depressed. This means that women’s continual engagement and letting go—of children, careers, and partners—prepared them well for the shifts of old age and could account for their greater flexibility and resilience later in life. Author Anna Quindlen had it right when she wrote, “…. women’s lives have been about re-definition, over and over again, while men’s lives are still often about maintaining the status quo.”

The Blessing Of Good Luck

We talk of the importance of having resilience, of finding passions and meaning in life. But another factor can play an enormous role in how our later years turn out: luck. The fortunate ones are bestowed with good luck. Others work hard, do the right thing, and yet do not get what they deserve. Life is not fair.

Alice Ladas, who is ninety-two, commented on how her good fortune contributed to her longevity when I interviewed her. She said, “The fact is, I have been lucky. I have not had a major accident or major health problem. I have not been run over by a car. I was not at the twin towers when they fell.” To some, that could make her an unsympathetic exception—rather than an exemplary person—because she has not struggled enough.

On the other hand, good luck alone might not be sufficient to create longevity. Sara/Hannah Rigler, whom you’ll also meet in these pages, observed that there is another step that must follow luck for it to be truly utilized. In her book she wrote,

“Some would say I have been lucky and I have—but luck only impacts if you grab onto it and use it to help yourself and others. (My emphasis) In an airplane the stewardess tells you in case of emergency to use the oxygen first, and then help the less able. I have spent my life following this admonition. I kept myself alive by resisting death when I left the line of the death march. I kept myself alive even when I fell into deep despair at the news that my mother and sister perished. I kept myself alive so that my family and my people would continue.”

Indeed, she has seized her luck and used it to keep herself and future generations alive.

The Jewish Connection

The Jewish attitude toward aging differs from the general attitude prevalent in twenty-first century Western society. Jewish views are based on a unique respect for the wisdom that comes with age and a reverence for our own parents and the elderly in general. The Torah commands that we respect all elderly, believing that the challenges and experiences they have encountered throughout their lives bring wisdom. The Torah also considers old age a virtue and a blessing and often equates “old” (zakein) with “wise.” Thus, a ripe old age is regarded as one of the greatest blessings we can experience.

Of course, we all endorse these beliefs in theory but they might not play out so consistently in real life. Older Jewish women still experience the ageism and sexism prevalent among all older women. The stereotype of the Jewish mother who is overprotective, nagging and guilt-producing remains alive and well. Clichés also abound for the kvetch (someone who is constantly complaining) and the demure, self-sacrificing widow.

These stereotypes are not far from the concept of crone, a stock character of an old woman in folklore and fairy tale. Sometimes she is portrayed as nasty or evil but often with magical powers. On the positive side, a crone can be viewed as an archetypal figure, a Wise Woman—not simply any older woman. In the last thirty years, many older women have begun connecting to the crone and her positive attributes: wisdom, kindness, and transformation. Identifying with this archetype affirms the knowledge, insights, and intuition that accompany aging.

The women in this book represent twelve different life experiences and twelve unique ways of aging with wisdom and vitality. I have chosen the number twelve because it is a significant one in Judaism. Twelve is considered one of the perfect numbers. Jacob had twelve sons, who were the ancestors of the twelve tribes of Israel. I hope the twelve women in this book will help replace some of the stereotypical figures with a more realistic view of older Jewish women.

About This Book

Although this book favors career women—at a time when it was not easy or automatic to go to college—the main criteria for selecting and profiling these women is their resilience and vibrancy in “older age,” regardless of their educational or career achievements.

To find women who met these qualifications, I began by sending an email to a select group of friends, acquaintances, and colleagues. I sifted through their recommendations and when I found someone who seemed well suited, I asked her to fill out a short survey so I could obtain some background information. The survey also asked some deeper questions, including: What were three major changes or transformations that occurred during your life and how did you respond to them? How did your earlier life prepare you for life as an older woman? How did your connection to Judaism impact on your life?

Their answers to these questions helped me decide whether the woman had the insight and thoughtfulness this project required. Once I selected a woman, I interviewed her for several hours (often broken up into small segments), sometimes on the phone and sometimes in person, depending on where she lived.

With the resilience research in mind, I focused on how they have adapted to change over the years and in their current life. I explored whether and how their response has shifted as they have aged, how the understanding they have gained has contributed to their longevity, and how they cope today with the transitions and losses that aging brings. I also delved into the ramifications of those changes on their lives today by exploring how these women see their old age as a product and reflection of the choices and adaptations they made earlier in their lives.

All the women in the book were born Jewish and are grandmothers. Most continue to practice Judaism today and strive for a spiritual life in some form. They range from observant to cultural Jews. Some have rejected organized religion but have incorporated the principles of Judaism into their lives and are living according to those standards. Others are still actively involved in synagogue life. One finds meaning in Jewish meditation; another has left the fold altogether.

Each woman has her own chapter. It begins with her photo as a way to combat the invisibility that so many older women feel. You can visualize her as you read her chapter and realize that yes, this is what ninety looks like. The chapter combines the narrative of her life with her thoughts and reflections about her experiences, excerpted from our interviews. Direct quotes from the interviewees are in italics. Each woman had an opportunity to read her chapter before it went to press so that she could check the facts.

“The Privilege Of Aging”

While many of us lament growing older and wish we were younger, the fact is, it is a privilege to age—especially when you consider the alternative. Coping with an aging body, losing friends and family, becoming ill: these take their toll. We all have unique ways of responding to these shifts based on who we are, what our earlier life has been like, and how we feel about ourselves today.

Actress Laura Linney coined the phrase “the privilege of aging” in a July 28, 2010 article in The New York Times. She talked about aging, and about how she was mystified and frustrated with so many people’s rebellion against aging. She conceded that “sagging skin, waning energy and creaky joints are not fun,” but said that the early deaths of beloved friends had opened her eyes to the fact that growing old is the greatest of blessings. “A lot of people do not get that privilege,” she said. “And there is an extreme disrespect toward that that is cuckoo.” Whenever she realizes that she is about to complain about aging, she imagines one of her friends who has died taking her by the shoulders and shaking her and saying: “Snap out of it!”

I hope that the twelve women in this book will inspire you and remind you that aging is indeed a privilege. Each of the women represents a different way of aging with grace, consciousness, wisdom and gratitude. Their willingness to share their life journey, including their triumphs over tragedy, is indeed a gift. On a personal note, I have accepted the fact that my mother was unable to give me the legacy of long years, and that I will never know why she died so young. But I realize now that she gave me a model of how to be a caring mother and grandmother, a supportive wife, and a good friend.

The women in this book also leave their legacies in many forms. Read about them and then select the women’s journeys that resonate with you. Make these women your role models so that the way you live your later years can be a legacy, and a blessing for your family and friends.

ISBN 9781935604525. Paper. 128 pages. $16.00

ISBN 9781935604532. eBook. Available on Amazon.

For information on group orders from Gaon Books

Call 505.920.7771

or e-mail gaonbooks@gmail.com

Distributed to the book industry by Ingram and others

Gaon Books

Excellence in Publishing