Click here to read a selection

from Pulling It All Together

ISBN: 9781935604013. Paper. 34.95. 596 pages

Gaon Books

Call 505.920.7771

or e-mail gaonbooks@gmail.com

Out of Print

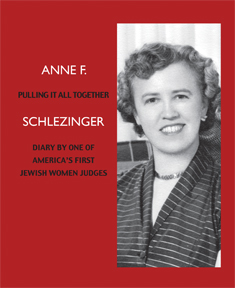

Pulling It All Together

Diary by One of America's First Jewish Women Federal Judges

Judge Anne F. Schlezinger

Shulamit Reinharz (Brandeis University) Introduction

Orit Rabkin (University of Oklahoma) Epilogue: The Art of Women’s Diary Writing

Reading Sample

When Anne Freeling began diary writing on January 1, 1931, she could not have realized that she was starting a half century long project of describing her life as a groundbreaking woman professional in the twentieth century. Forty-seven years later she had narrated the five central decades of the century that transformed American life, the decades that saw the country change from struggling in the Great Depression to its role of world dominance and wealth. Anne was near the center of power in Washington, D.C., and major national events appear in her diaries, but in her daily entries she focuses on personal concerns of her life and family. Although she was involved in major cases of labor law and media churning political events, she writes in more detail about her personal life. It was a private area, safe and tranquil. On events that we now see of major historical significance, her comments are frequently cryptic and short. When her emotions creep through, she is usually writing about personal issues with her family or the frustration with the slowness of her job promotions. Only when she fell ill with lymphoma in December, 1977 and had to enter the hospital did she falter in writing daily notes. After a two month lapse her last entries were made in April and early May, 1978, when she rallied briefly before she fell silent.

Anne was born in 1910 of Jewish immigrant parents from the Ukraine. The original spelling of the family name was Frihling, but it was later anglicized to Freeling. Throughout her diaries we read about her sisters Clara and Jean, who later changed her name to Janet, and her Mother (Regina) and father (Abraham). Her brother Louis (sometimes called Louie) died in World War II in action in Europe. Her grandmother, Baba Wagshal, was an important presence in her life, and in her early years in Washington the family of her cousin, Sam Wagshal, was important. Her diaries from 1931 to 1952 tell the story of an intelligent young woman who had little patience for the frivolity of the young people around her. She was focused and determined to be a lawyer, but she worked in a world that favored neither Jews nor women in the profession that she had chosen. After she completed law school and passed the Bar the only job she could get initially was as a legal secretary. Later, she was able to get a job as a lawyer with the federal government.

In Washington D.C. she encountered a larger Jewish community and professional world. Her friends were increasingly Jewish, and she eventually met and married a fellow lawyer from that group, Julius Schlezinger. They worked together, and she respected him intellectually. Anne was unable to have children, so they adopted a son, Ira, who transformed her life. Anne repeatedly expresses her emotional identity with her family, her love of Jules and Ira, the torment with her mother, and the bond with her sister, Clara.

In World War II Julius volunteered for the U.S. Army, which lead to a long, lonely time for Anne filled with anxiety. She narrated her feelings and her growing affection for Julius during that time. After the war the two of them returned to their work and professional lives, and realizing the post-war dream they moved to a house in the suburbs. Then, the election of Eisenhower as president in 1952 led to a turning point in their lives. Anne lost her position with the National Labor Relations Board with the new administration; she challenged through an appeal, which led to her reinstatement. In the 1960’s she reached professional success with her appointment as an NLRB judge.

Although Anne writes about her professional life, it is within the context of her personal life. It was an important component of her complex network of friends, colleagues, and relatives, all of whom were woven together in the fabric of life through lunches, dinners, social visits, cultural events, and vacations. Although she was spare in describing the emotional details of her life in her entries, there were times when her emotional concerns slipped through. In the 1940’s and 1950’s she repeatedly questioned herself as a wife and mother, especially in relation to work. At those moments she would reveal the push and pull between her sense of family obligation and commitment to being a professional woman.

The diary entries are a chronicle of her social life, friends, and meals. Many entries are punctuated with references to breakfast, lunch, and dinner. She loved the social context of lunching and dining and regularly identifies locations, companions, and the food itself. Through this chronicling of a life over five decades we can see many of the social, economic, political, and ethnic changes that occurred in the United States during that time period. We see the changes from radio to television, from public transportation to private cars, from urban living to suburban life, and the economic expansion of life that occurred during those years.

The analysis of her diary shows the evolution of her interests, as she grew from a young law student in a pre-feminist era to a judge in a prominent national agency. Although Anne was deeply involved with worker’s rights, she seems not to have been involved in women’s rights movements. There is no evidence of her being a member of the National Council of Jewish Women, and she does not mention the work of Hannah Solomon in favor of Jewish women’s rights. She makes oblique references to the larger women’s rights movement but does not seem to have been actively involved with it.

As early as the 1870’s the first women in the United States were becoming lawyers (Leary 2009), and by the beginning of the twentieth century women were making a concerted push to gain entrance to the legal profession. The National Association of Women Lawyers was founded in 1899 before the American Bar Association would accept women. The Women Lawyer’s Journal, which was started independently in New York in 1912, eventually became the publication of the NAWL. Early issues of the Women Lawyer’s Journal show that women lawyers were teaching in law schools, and there were women lawyers and judges in the areas of domestic relations, children’s, and juvenile law in local, municipal courts. By the 1920’s most law schools were admitting women at a time when women had just earned the right to vote.

Although women could study law and pass the Bar, many bar associations would not accept them as members. The Maryland State Bar Association did not admit women until 1946, and the Bar Association of Baltimore did not admit women or African Americans until 1957. Ruth Bader Ginsberg mentions that in the mid to late 1950’s she was one of nine women in a law school class of 500 men (1978:1ff). Harvard Law School did not admit women until 1950 (Leary 2009). Many of the barriers against women in law were late in falling.

Anne was one of a group of women lawyers who were edging their way into the legal profession in the early and mid-twentieth century, and she represents the early group of women to obtain positions as lawyers at the Federal level. In the 1930’s Anne worked in the Department of Labor under Francis Perkins, the first woman to be named to a cabinet post in the United States government, and she met Secretary Perkins personally. Anne assumed that she could have any job that a man could have, but she was thirty years too early to reach her potential and her expectations.

The National Labor Relations Board was in the lead hiring women lawyers and later in naming women as judges at the Federal level. Anne and Fannie Boyls were hired as lawyers by the NLRB in the 1930’s when there were few women in such positions. Eventually they were in the first cohort of women judges along with Rosanna Blake and Josephine Klein in the 1960’s. At the time of Anne’s death in the late 1970’s women judges were being named to the Federal courts. Although President Gerald Ford made some such appointments, between 1976 and 1980 President Jimmy Carter named forty-one women to the Federal Judiciary, which is considered the first major breakthrough for women at the national level.

Anne writes modestly about herself, and with career achievement limited by her sex, she focuses on social contacts, lunches, and dinners in detail, reflecting a complex social circle. In sequences of considerable emotional depth she questions and evaluates her feelings toward her suitors, including her future husband, before getting married. Her writing reflects the delight she took in working and the social life associated with it, but she continually questions how that affected her obligations as wife and mother. Anne suffered from migraine headaches that could be debilitating, and she makes occasional references to lost days because of those headaches.

Anne Schlezinger’s diary gives a personal day-by-day narrative of the building of the American Jewish professional class of the Great Generation. Like many others of that time period, she lived through the sacrifices of the Depression and World War II and focused on achievement in her life. Sometimes as a reader, we want more information, and then subtly, almost without knowing it, we realize that she has perhaps given us more in her unassuming way than we were able to realize. It is in the details of lunches and dinners, parties, shopping trips, office meetings, trial hearings, and conversations with friends and colleagues in almost 20,000 diary entries that we realize the legacy of information about life during her time that she has left for us.

This diary is largely an account of her social networking throughout her lifetime. At times she ignores or gives only passing comments to historically important events, but her daily record of the people with whom she had coffee, lunch, and dinner is meticulous. She was superb at networking before we had a term for it.

As a twenty-year-old student in 1931, Anne was living in a rooming house in Boston with other young women, supporting herself working as a stenographer during the day and studying law at the Northeastern Law School at night. Her family was not wealthy, so even as a young law student she worked and lived on what she earned.

Anne grew up in a family in which English was not the first language, and in her diaries in the early years her spelling is weak, and for much of her life she struggled with the spelling of unfamiliar last names. She had entered law school directly out of high school in the middle of the Great Depression. Although she occasionally mentions people losing jobs or economic difficulties, those references are rare. In her diary entries from the 1930’s we see her interests, fun, and endeavors as a student. She completed law school in 1933 and passed the bar exam shortly afterwards.

As a young Jewish woman lawyer, she had no professional opportunities in Boston that matched her ambitions, and she moved to Washington, D.C. Even there she could not get a job as a lawyer, so she begin working as a legal secretary with the expectation of eventually getting a professional position.

The most important person to her in the early years was her sister Jean, whom she mentions once or twice daily. The two sisters had different temperaments, so that Anne was frustrated that Jean was not more like her. She had little patience with the young men and women around her, who were more interested in dancing and drinking than more serious matters.

Then, in 1932 Charles Wyzanski, a lawyer in Boston, begsn to appear frequently in the diary and continues until late in the decade. For Anne, emotional and professional ties were intertwined with Wyzanski although she always refers to him in professional terms in the diary. By 1933 he was in the U.S. Department of Labor in Washington, D.C. and arranged a job for Anne there. It was on her application for that job that he learned that she was Jewish. Anne was twenty-three years old at that point and for years she thought that a relationship might develop between them. It never happened. In this volume some 1,800 entries have been selected from important time periods, representing each year of her life.

Ron Duncan Hart, Ph.D.

Cultural Anthropologist

Gaon Books

Excellence in Publishing