Follow

Gaon Books

on

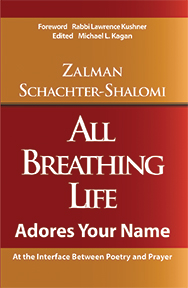

All Breathing Life Adores Your Name

Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi

Michael L. Kagan, editor

Introduction

Jewish Sacred Poetry

Why Do I Want to Share This?

I remember how dismayed I was whenever I saw an anthology of spiritual writings in which there was a lot of material from Hindu, Sufi, and Christian spiritual writers, and in vain did I look for Jewish writings that would show heart, soul, and spirit. I knew well that they existed, but alas, only in their Hebrew originals. I was also aware of the fact that many of the editors of Jewish prayer manuals often translated or rendered the original liturgical material to be read by the discursive mind. However, the original Hebrew was never meant to be scanned silently with the eyes alone. There is something about sacred poetry that demands chanting in such a way that the words will arouse feelings in the heart of the worshiper.

While Martin Buber, in his amazing and powerful work I and Thou, made it clear that in the immediacy of the human-Divine encounter we were not dealing with objects, and thereby brought us into the sense of the dialogue, there was little understanding on the part of his readers of the right brain and left brain difference.

If I were to speak of this from the point of view of the Kabbalah and the Four Worlds, the people who worked in Jewish scholarship – Judische Wissenschaft – were all dedicated to showing how Judaism was a “religion of reason,” in the Kantian sense; and even if they did touch poetry, it was only for the sake of analyzing it to be at the service of the rational mind. They only operated in the world of Assiya (deed), dealing with grammar and history, or with the world of B’riya (intellect) with the concepts touched by the poetry.

A poet does not write in order to present the linguist or art historian with a word-cadaver to dissect and catalog. The poets, possessed by the Daemon, the devotional Muse, find themselves captivated by enchantment, and such enchantment they wish to share with others. The poet is attuned to an imaginal reality that exists in a world of its own. The reader can choose not to enter into the world of the parable, the Olam HaMashal, but, as Kafka pointed out, all he has then gained is entrance into the world of things.

Spiritual poetry is a launching platform to take the person who will lovingly recite it into another realm. Those of us who are acquainted with the second part of the daily Hebrew prayer service known as P’sukei de-Zimrah and have been able to enter into it have learned to give thanks for the privilege of joining King David and the Levites in the Temple in the Yishtabach prayer (pxxx). The lover of God wants to express his or her longing for intimacy with the Beloved with the sounds of niggunim, and the words that accompany them. The more they can enter into the reality behind the words, the closer they will feel to the Divine Presence.

While sensation deals with things, and reason with concepts and ideas, neither is in the dialogical position. The one who wants to face the living God—in the Shiviti—needs to do it with the heart. However, the heart needs an Other; it needs to be in relationship. In this way, sacred poetry becomes a password to a tryst with the Beloved, bringing one closer to facing the Divine Other. (Even if philosophical reason is anchored in an absolute monism in which there is no Other, the heart must nevertheless set reason aside in order to encounter the Beloved. In my poem, “Beyond I and Thou” (pxxx), I made an attempt in my poem to satisfy both heart and mind.)

What Were My Motives?

As I said, very seldom were we able to find translations of hymns and prayers that spoke to the heart. In Great Britain, in the Victorian era, there were some beautiful translations made that echoed the language of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer. The early American Reform Movement did likewise in its hymnal. There were times when I would joyfully sing: “Come O Sabbath day and bring—peace and healing on thy wing—and to every troubled breast—speak of the divine behest—thou shalt rest, thou shalt rest.” It had the power to move me emotionally, as did: “At the Dawn I seek Thee—Refuge, Rock Divine.” Perhaps it was my Hapsburg origins, but I found that I was alone; others did not feel the same way. The language was too stilted, the imagery too archaic. The God we want to encounter is not so regally formal. Isn’t it incongruous to want to be hugged by the sovereign deity in front of all the Angels and heavenly saints? Contrast this to when we enter the Divine Presence through the eroticism of the Song of Songs saying: “Kiss me with the kisses of your mouth; your loving is more intoxicating than wine.” Once having discovered those precious moments of elation in the tryst with God in one’s heart, one can no longer be satisfied with the formality of the Victorian English. So how could I render the feelings of longing and closeness that I felt as I recited the Hebrew devotional love poems?

It is for this reason that I first felt the very strong need to translate Yedid Nefesh of Eleazar Azikri. Similarly, I found the usual translations of the An’im Z’mirot stodgy and lacking the devotional intent that the Hasidei Ashkenaz originally imbued it with.

I was mostly guided by introspection to the feelings of fervor I experienced in prayer, in reciting the Psalms and in chanting the poetry. So when I veered from the literal denotative meaning of some of the words, and allowed myself the freedom to express those connotations implied within the original Hebrew words, I felt that I had the right to place them on the page in that way.

Aesthetics have a way of changing with the changing culture. One only needs to listen to the popular songs of this generation to recognize what language would allow the generation to feel sacred enchantment.

I can’t possibly name all the people with whom I shared these materials and who helped me to refine them. The numerous weekend retreats and workshops, High Holy Day services; all of these were vessels in which these poem-prayers matured, allowing them to take on the deep flavor of the many souls who prayed them, sang them, and cried tears through them.

And how could I not be overflowing with thanks to Michael Kagan for his continued interest in bringing these efforts to a larger audience? I’m grateful to God that I had the privilege of sharing with him and his wife Rabbi Ruth Gan Kagan. They have become the vital connectors for Israelis to Jewish renewal.

And to my student, friend, hevruta, apprentice, teacher, Netanel Miles-Yepez, who sits so well-balanced on the three-fold fence, and without whom so much would not be done – my eternal thanks.

Nishmat

All Breathing Life Adores Your Name

There are times when I feel that I need no other prayer than the Nishmat. I prefer to take my time with it. I take each phrase, tasting it as I pronounce it, and then spend time in my imagination bringing it to life in a loving way so that I feel it in my heart. To enter into the prayer of Nishmat is to enter the enchantment of the miraculous order. Try reading it slowly and out loud so that you can hear and stress the sense of the second person, the I facing the Thou, addressing the God in whose presence you are.

All breathing life

adores Your Name;

Yah, our God -

All flesh alive

is raised to ecstasy

each time we become aware of You!

Beyond endless Time and Space that’s vast

You are Divine.

Only You are the One who

ultimately extricates and frees,

ransoms, saves and sustains us

and cares when we are in distress;

You, You alone secure our lives.

You, ultimate Cause and ultimate Effect,

Source of all Creation;

You manifest in all birthing.

In every compliment it is You we praise

You manage Your universe with kindness -

with compassion all beings in it.

Yah ever awake and ever alert!

You rouse us from the deepest sleep

You give words to the speechless

You release the imprisoned

You support the stumbling

You give dignity to the downtrodden

Every appreciation we offer is Yours.

If ocean-full our mouth were with music

Our tongues singing like the ceaseless surf

Our lips praising You to the skies

Our eyes blazing like sun and moon

Our arms spread like soaring eagles

Our legs sprinting like those of deer

We could not thank You enough

Yah! Our God, our parents’ God!

Neither could we celebrate by naming

the times exceeding millions

the places exceeding billions

the favors You did

for our parents and for us.

Yah! Oh God!

From oppression You redeemed us,

Now we can never be at home in slavery -

During famines You fed us enough

to live on

You shielded us from wars and plagues,

From diseases of body and mind

you pulled us out.

To this moment Your caring helped us,

We never lacked Your kindness –

Please don’t ever abandon us God!

Our limbs each want to thank you,

The air of each breath You breathed into us,

Their very substance bless with gratitude

with praise and celebration

honoring that exalted holiness

so majestic, that is Your fame!

Our speech is appreciation

Our expression an oath of loyalty

Our attitude surrender

Our stance before You obedience

Our feelings overwhelming awe

Our inners singing scales of Your Names

As it is in Scripture:

All my very essence exclaims:

Yah! Who? Like You?

You inspire the gentle to stand up to the bully,

The poor disempowered to stand up to the thug.

No other can claim to be what You are

No other can pretend to be

THE GREAT GOD

THE MIGHTY, THE AWESOME,

THE GOD, MOST HIGH

Yet nesting in Heavens and Earth!

So we will keep celebrating and delighting

and blessing Your Holy Name with David:

“Yahhh! breathes my soul out to You.

All my inners pulse with You!”

Potent God Force!

Magnanimous in Glory,

Ever prevailing,

Awesome Mystery!

Majestic One, who presides over all destiny!

Eternal Sh’khinah, Holy Beyond,

Saints sing Yah!

In harmony with decent folks.

Good people exalt You,

Saints are Your blessing,

Devotees sanctify You,

You delight in our inner holiness.

For further information or group discounts

Call 505.920.7771

or send e-mail to gaonbooks@gmail.com

Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi

To hear Rabbi Zalman chanting prayer/poems from this book, click on his photo or HERE.

Michael L. Kagan

is a teacher of Holistic Judaism and author of the Holistic Haggadah (Urim) and God’s Prayer (Herder). He is ordained as Maggid (teller of Holy Tales), Moreh (teacher of Torah) and Mashpiah (spiritual intervener). He has a PhD from Hebrew University.

Gaon Books

Excellence in Publishing